Friday, February 17, 2017

The Pillowman

As I have probably mentioned, I don't see many live shows, nor do I often go to theaters to see new movies. I simply don't make enough money to afford the luxury, so I must be extremely selective. This means that I often miss shows that my friends are doing, which is regrettable as I know that disappointed feeling I get when my people don't come to my own shows. I say all this to say that Life in Arts' Production of Martin McDonagh's The Pillowman is that rare gem that almost perfectly meets the criteria of my meager budget, and I have no regrets on seeing it, financial or otherwise (although I do have a friend who regrets not noticing that a student discount was available).

The Pillowman is set in what the Dramatists publishers describe as "an unnamed totalitarian state." Now, normally I reserve my negative comments for the end of a review, but I have to structure things differently, because the problems come up right away. When you, the audience member--part of a group that is potentially as diverse as our nation itself--walks into the Headwaters lobby, you see a sign by the concession stand that proclaims, "No Ban! No wall!" In the weeks prior to the opening of The Pillowman, the company--along with many other theatres across the country--participated in something called The Ghostlight Project, which was a solidarity movement among theatre artists to be a source of "light for the dark times ahead." You know, the dark times that will inevitably be brought on by our new President. Director Jamie Rea put her political cards right on the table in her program notes, essentially suggesting that since the election of Donald J. Trump, we now live in such an "absurd Kaftaesque totalitarian dictatorship". According to the program (but not the play itself), this piece is set right here and now. And if, dear audience, you did not pick up on this subtle message, you are provided with a picture of the President himself right there on the wall of the set. At the time of this production, President Trump has been in office less than a month. Such politicization and pandering is unnecessary, distracting and, frankly, beneath the otherwise excellent work by this company. Instead of just presenting a play and allowing the audience to draw its own conclusions, the audience is getting a personal, partisan agenda from the theatre company and being told what to think, which--in a manner I suppose is completely unintentional to the artists--goes right along with the play's themes.

In a way, the totalitarian theme is a bit of a red herring, a plot point that doesn't seem to really go anywhere. This is not the fault of the production, but possibly a flaw in McDonagh's play itself. I am probably wrong; it just seems to me that it's explored a tiny bit and then fizzles out after the first act. Unless you're just talking about police brutality and lack of due process, which is something that has unfortunately existed in every government throughout time. None of that is earth-shattering.

This is the story of two brothers who are accused of murdering three local children. They are locked up and interrogated by a couple of heavies (Bobby Bermea and Jonah Weston) who seem to feel that a person is guilty until proven innocent, and even then, perhaps still guilty under their law. The brothers are Katurian (Benjamin Philip), a writer of dark fables involving children, and Michal (Gary Strong), a mentally disabled man, a year older. The reason the two are suspected of the killings is because they closely mirror the short stories of Katurian. In fact, the stories seem to serve as an inspiration and blueprint for the violence.

To reveal much more of the plot would be a great disservice to the audience. The brothers have a horrific background, a childhood that no doubt inspired the dark writings of the protagonist. The play explores how we are shaped by the experiences of our childhoods and--in light of that--how much responsibility we bear for our actions as grown-ups. It also explores the nature of the creative mind, how an artist is defined by the work that they create, and how closely artists guard and protect their work as sacred. (I can relate to this a great deal.) And, to go even deeper, it asks if an artist (in this case a writer) has any responsibility to his/her audience in regard to content and the possible reaction to it. I was reminded of the story of a school shooting that led Stephen King to take his book, Rage, off the market when the book was discovered in the shooter's locker.

If I could think of one word to describe the acting performances in this piece, it would be "brave". Not only are they dealing with one of the most disturbing topics is existence--the brutal killing of children--but they do it in a very straightforward way, never flinching (unless of course it's natural for the character to do so), and you've got actual children on stage acting this stuff out. I feel this play would disturb the sensibilities of many parents. But McDonagh is a writer who goes for the jugular (so to speak), and in order for a production to work, the acting ensemble must be willing to do the same, and every single one was up to the task.

I did kind of wonder about the character of Michal, who seemed to shift in his levels of maturity and understanding. Sometimes he seemed to have the IQ of a toddler, and other times he was surprisingly astute. It seems like a mild inconsistency, but I'm not prepared to call anyone out on it, because it may be quite intentional. It's the type of thing I'd have to examine with repeated viewings, which, of course, is not possible.

There is a lot that could be said about the original music, sound design, lighting design, set design, props, staging, costumes, makeup, etc. Look, this is top notch work, and I was impressed enough to even be a little envious of what this crew has pulled off. All the different elements work so well together and add to the overall tone of menace and dread. The night I saw it, there were some timing issues with the sound cues, but from a design standpoint, it was absolutely amazing, and I loved virtually everything about it.

I should note, for anyone who worries the play might be too dark, there is actually a lot humor in it. Humor is an absolutely essential element in a play of this nature; otherwise audiences might indeed lack the stamina to endure such a long and deep reflection on human nature's darkest corners.

The Pillowman runs through February 25th, Thursday through Sunday at 7:30 at the Headwaters, 55 NE Farragut St. Ste 9 in Portland. Tickets: https://squareup.com/store/life-in-arts-productions.

Sunday, January 22, 2017

The Falls Trilogy

As a gay

Christian artist, I have spent over 20 years exploring the relationship between

spirituality and sexuality, and the various conflicts and struggles that exist,

of which it seems not that many people are fully aware, even now. It’s a web of complex

issues that is not strictly black and white. Many people, of faith and not of

faith, believe that you have to choose one or the other, and do not understand

the challenges faced by those who refuse to accept that mandate. When I first

saw The Falls, and as I’ve followed the trilogy to its conclusion, I had a

mixed emotional reaction to it. On one hand, I have felt jealous and frustrated

that someone else has, in a sense, beat me to the punch in dealing with these

issues in an extremely effective and satisfying way. Why could it not have been

me? (The answer has to do with my lack of professional connections, confidence,

giving up too quickly, etc.) But on the other hand, I am awestruck and inspired

by this series of films that I truly believe everyone should see because they

are some of the finest and most important works ever made on these topics. Many

have tried before, and have fallen short. I won’t leave you in suspense. This is

a most positive review. I will talk about why these movies work so well, and

include some personal stories along with it.

Note: There

will likely be some mild spoilers here, but nothing that would really ruin the

enjoyment for people who haven’t seen the films. Just be warned though. I want

people to see these movies, so if you think you shouldn’t find out a little

ahead of time, see them first, then come back.

The Falls (2012)

When I saw

The Falls for the first time, I didn’t realize that it was filmed in Portland

until I saw local actor Brian Allard about a third of the way into the film.

Later on, I would see Harold Phillips, who I know from way back when I stage

managed a production of Speed the Plow that he starred in back in 2000. When

you realize that something was done in your back yard and you didn’t know about

it, you have kind of an “aw shit” moment, like, “I wish I could have been

involved in this”, but truthfully I’ve never been involved in film, only

theatre (though I write screenplays). Some of my readers know I went to film

school and it did not agree with me. At all.

The Falls

tells the story of two young Mormon men beginning their obligatory 2-year

missionary work. Apparently, they are paired up (they are called each other’s "missionary companions") and end up rooming together, dorm-style. They receive training

and practice in the evangelistic work that they will be doing.

Not

surprisingly to anyone watching this movie, but surprising to the characters

themselves, the two men (Chris, played by Ben Farmer) and RJ (played by Nick Ferrucci)

form a very strong attraction and subsequent bond with each other, which leads

to sexual intimacy. And not surprisingly, it turns their world upside down

because not only do they have to wrestle with their own internal conflicts, but

they also have a huge secret they must keep.

This film

provides an interesting primer for people who are completely ignorant about the

LDS church and what they believe. We see Chris and RJ talking to so-called “investigators”

who are curious and sometimes skeptical, even critical, about their beliefs. We

see what it’s like to have to explain and defend your beliefs to people who

think you’re basically nuts. You also get to see things like Mormon underwear,

which I’d never really seen…in fact, I didn’t know such a thing even existed. I

just thought, Boy, these guys have some heavy-duty industrial knee-level

chastity underwear that looks like it should also come with a padlock or alarm system

should anyone come close, like Princess Vespa in Spaceballs. Not very erotic,

but the film manages to find plenty of eroticism anyway. It doesn’t hurt that

the two leading men are lookers.

We get a

curveball in the Brian Allard character, a pot-smoking Iraq war vet with PTSD,

who RJ and Chris get to know as part of their outreach. Rodney (Allard) is not

religious at all, and on the surface, looks like a potentially bad influence on

these two young men of God. Indeed, by film’s end, he’s got them smoking pot

and watching R-rated movies. A change starts to take place in these characters’

lives as they reexamine their priorities, which affects their performance as

missionaries and jeopardizes the secret relationship that they share.

Soon comes a

crisis point. I won’t say what it is, but it’s fairly predictable, inevitable

really. Soon we meet the families in the wake of said crisis, as everyone must

decide where to go from here. We meet Harold Phillips, who is Portland’s answer

to Tom Hanks, that affable guy whose face is always welcome in any movie or TV

show. He plays the father of RJ, who is the more fortunate of the two lovers in

that he has a fairly supportive family that is capable of adjusting. Chris does

not. All of a sudden, the romance between the two men is subject to the

dictates of God, the church, family, friends, and probably the dog as well.

Will it survive? Who can know?

And that’s

where they leave it. And to think, writer/director Jon Garcia—who is neither

Mormon, nor gay—wasn’t originally going to follow it up with a sequel. But his

film resonated with people, much more so than he could have imagined.

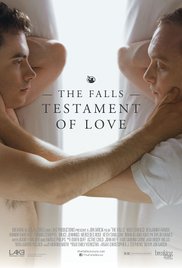

The Falls: Testament of Love (2013)

Part 2 is

the most challenging of the trilogy, both for the characters themselves and for

the audience. It’s an excellent film, but it is not an easy film to watch; it

is actually grueling at times. And it is due to the honesty and the genuine

humanity that is shown in every well drawn-out and nuanced performance.

Five years

after the events of the first film, RJ and Chris have moved on with their

lives. Chris has been pressured into reparative therapy, which paved the way

for a marriage with a beautiful woman (Emily, played with real tenderness by Hannah Barefoot), a

marriage that seems happy, but the audience—who always knows more than the

characters do—understands it’s an ill-advised union based on lies and

self-denial. They even have a kid and a lavish house, which is not quite as

nice as the one the Cullen family owned in Twilight, but almost. (Where are

these beautiful local homes, wonders the Portlander.)

RJ has also

begun a new relationship with personal trainer Paul (played with heartbreaking vulnerability

by Thomas Stroppel), and they reside in Seattle. The relationship isn’t perfect.

You get the sense that Paul wants to change RJ in certain ways, to mold him

into what he thinks he ought to be—eating better, exercising more, etc. It’s

nothing compared to the pressure that Chris is enduring, but there is an

unsettling disparity in terms of what they both want from the other, in spite

of the very real affection that is apparent in their interactions.

What

reunites RJ and Chris is the death of their old pal Rodney of cancer (although

the cancer is only explained in a deleted scene; in the theatrical cut, I don’t

think we even know what he died of). It’s an awkward reunion, and Chris has

repressed his sexuality to the point of hostility towards RJ when it’s brought

up. That hostility is intensified a few weeks later when RJ decides to take a

trip to Salt Lake and drop by Chris’ house uninvited and unannounced in the

middle of family dinner, setting off a series of events that threaten to blow

up Chris’ family to smithereens.

One of the

challenging things about this series—and most particularly, this installment—is

that these people are revealed to be not constantly lovable paragons of virtue,

but really deeply flawed human beings, sometimes incredibly selfish, incredibly

reckless and irresponsible. There are several actions taken by both Chris and

RJ that may seem very wrong to some viewers, including myself. You want to root

for these people, but you sit in front of the screen just a little aghast at the audacity of some of these choices that are made. “Why did he just do that?!”

you yell to yourself. And even I had to remind myself that these people,

through no fault of their own, have been put into an extremely difficult

circumstance, in which their very faith and eternal salvation may be at stake,

not to mention their relationship with their families and communities, and

balancing with that the question of the very legitimacy of true love. In

extreme circumstances, people respond in extreme and desperate ways. You can’t

really judge them too harshly because you can see every fragment of love, fear,

anger, confusion, and despair in the faces of both RJ and Chris (in some of the

most truthful and sensitive performances I’ve ever seen from Ferrucci and

Farmer, who should go on to become enormously successful and famous because

they deserve it). The same goes for the heartbroken Emily and Paul, who had

the misfortune of being forced rebound relationships doomed to destruction by

the on-again, off-again chaos that is this tortured romance.

There isn’t

any hero or villain here. You genuinely come to feel for every character in

this story, much more than in Part 1 because the stakes are so much higher.

There is no way for anyone to come out of this unscathed, no way to avoid pain

and heartache. Whose fault is it? Some of it lies in the church and the belief

systems that oppress its members, but it also lies squarely in the hands of our

protagonists, who don’t know how to find peace and happiness in a way that

avoids running over the people they care about.

Not a

feel-good movie, but a powerful one.

The Falls: Covenant of Grace (2016)

First off,

one of my favorite film titles, ever. And very appropriate because if anyone

needs grace, it is Chris, RJ, and their families.

In between

seeing Part 2 and the filming of Part 3, I reached out to Ben Farmer by email,

telling of how much I admired these movies. I’m one of a great number of people

who have done this, generating the overwhelming response that encouraged the

making of both parts 2 and 3. My friend Michael Stringfield, who produces

sports programming but does occasional commercials on the side, asked if I

would be an extra in a shoot for Eastside Distillings Burnside Bourbon, and

because I have a hard time saying no to anything Michael asks of me, I showed

up at this bar, and was surprised to see Ben Farmer as the main character in

the commercial. It was a weird day because I felt like this closet groupie

wannabe fanboy, wishing I would will myself to go schmoose with this actor that

I was so impressed with, but I was too shy to do so. I resolved that he would

someday act in one of my stage productions, but I would soon find out he was

moving to New York. A few months after that, they started filming Covenant of

Grace, and again part of me wished I could be an extra or something, but stayed

away. I didn’t even attend the premier, which wasn’t a real premier because it

was unfinished, but Farmer and Phillips were there, and it would have been fun.

Personal

story aside, this takes place a year after RJ showed up in Salt Lake and tore

Chris’ family apart, then left him alone to deal with the fallout. They do

reconnect, and again, a death serves as a catalyst to the changes that happen in

their relationship. This time, it is Chris’ beloved mother, who was supportive

of him back when his dad was so harsh and judgmental. We see the life that RJ

has built for himself in the last year, now in Portland. He’s got a pair of

lesbian friends who seem a little out of place in this story. (Garcia has given

them a lot of backstory, not all of which is included in this film to help the

audience understand why they’re even there, and if fact, they should probably

just have their own film.) Another new character is Ryan, a younger man who

looks up to RJ and, in fact, has feelings for him. All these performances are

very strong, especially Curtis Edward Jackson as Ryan, whose story closely

mirrors that of Chris and RJ’s. But excellent performances are no surprise at

this point; they are par for the course in these films. You’ve got to credit

Garcia with having an eye for raw talent and clearly a gift for bringing out

amazing work in his actors.

For the

first time, it seems as though Chris and RJ have a real chance at the

relationship that has eluded them for so long. Their family’s views are

softening (with the exception of Chris’ angry brother, played by Andrew Bray in

a role that may be one of the weakest in terms of the writing…Why didn’t Garcia

give this character more dimension than homophobic anger and hostility?). But

the church’s stance has been the opposite. Now there is a new proclamation from

the church which states that children of gay couples can’t be baptized. This

triggers the central conflict of this third installment, which is RJ and Chris

having to finally answer for themselves that question that has been hanging

over them for 7 years: how do they reconcile their faith and their love for one

another? Can they have both?

If that was

the only issue that this movie takes on, it would be a little redundant and

tedious at this point because, like I said, it’s been right there in front of

them the whole time. But this is a movie about relationships more than anything

else. It’s not about preaching social, religious, or political viewpoints. It’s

about the process of self-discovery, figuring out what you really want, what

you really believe, and how you want to treat the people in your life. In what

is arguably the most powerful scene, which oddly doesn’t even feature Ben

Farmer, RJ and young Ryan are exploring their feelings for each other, and instead

of just following the passion of the moment and the true affection that the two

share, like you would expect from RJ (because, you know, we think we know him

pretty well at this point), RJ puts on the breaks, realizing that taking that

relationship to a physical level would only hurt Ryan because of RJ’s

unresolved feelings for Chris, and because of Ryan’s similar situation with his

own former missionary companion over which he pines day and night. This is a

real evolution for RJ’s character, and it’s incredibly refreshing.

Chris has a

similar moment with his father, from whom he has been seeking approval all his

life. Once he gets it, he realizes that’s awesome, but even if that had not

been given, he had come to the place where he could make his own decisions and

be at peace with them.

Eventually,

RJ and Chris decide what they’re going to do. Will they be together, at last?

Obviously, I’m not going to say. What I will say is that Covenant of Grace is a

satisfying conclusion to this beautiful and emotional story.

So what more

is there to say about these films that I haven’t said yet? For me, it’s all

about honest, totally invested performances, characters that feel so real that

you almost believe you know them personally. It’s also the writing. While this

material could have come across as fairly pedantic, Jon Garcia seemed more interested

in telling a compelling story than in preaching any particular point of view. There

are Issues, but they always take a back seat to the relationships, and that’s

how it should be. That’s why I think a lot of films of this type fail is

because they are throwing a sermon at you instead of engaging you in a very

personal and relatable story. There is so much honesty and truth in these three

films, it would take a hundred mainstream Hollywood movies to match it.

See these

films. See them with friends and family. And then have them encourage others

to. And, you know, I’ll get mine out eventually.

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Denial by Richard Strife

How do you escape an unhappy life? For Rebecca Silas, the young woman at the center of Richard Strife’s debut novel, Denial (Book I of a series called The Drakeon Chronicles), the answer is desperate and extreme. It is not enough to leave the man she’s about to marry at the altar; she’s going to leave this whole world behind. Fortunately for her, she has an annoying little brother named Alex who stops her in the act. But escape still comes in the form of a ghost dragon that appears out of nowhere and whisks Rebecca and her brother into a mythical world called Gaedia.

So begins

one of only a few fantasy novels that I have read. I generally avoid them

because they require more concentration—and perhaps even a little more

imagination—from the reader who must memorize all kinds of foreign-sounding

names, places, and things, in addition to filling in a lot of the mental details

about descriptions of creatures and landscapes because if the author were to

take the time to create a truly vivid picture for the reader, the novel would

be 1,000 pages long. (And yes, I realize some are, and many fans have no

problem with it!) One of the greatest

strengths of Denial is that it is

accessible to folks like me, who usually prefer reading about the familiar to

the otherworldly.

The idea

that you can accidentally step through an unknown portal and end up in another

world (or, in some cases, a parallel universe) is not a new one; it’s a

tried-and-true convention of the fantasy and sci-fi genres, from Star Trek to The Dark Tower. It works best when the starting point is that place

that you’re familiar with already. It grounds you in the story and characters

so that when it’s time to take the journey to the unknown, you’ve got something

that feels concrete to hold onto.

When Rebecca

and Alex arrive in Gaedia, they find a world in extreme conflict, where dragons

are massacring the townspeople left and right, in violation of an old treaty.

We meet the handsome, charismatic prince Sebastian, who chases one such dragon

away with his mind control abilities. Sebastian is on a mission to find his

missing father, the future Emperor, but he also needs to get to the bottom of

what’s going on with these attacks. Meanwhile, Rebecca meets a wounded female

werewolf—or Lykos—called Kaece, who she helps flee from town undetected. Sebastian’s

people, the Maedians, and the Lykos share a mutual hatred for one another. This

is a central conflict in the story, as Rebecca and Alex need Sebastian’s

protection in the wild continent of Xiratera, but Rebecca has formed an

immediate and obsessive affinity with Kaece, which could prove deadly.

As Rebecca,

Alex, and Sebastian travel the continent in something called a Hadros (a

vehicle that will likely remind the reader of the All-Terrain Armored

Transports used by the Empire in the Star

Wars films), with a dangerous and seductive Lykos on their tail, they will

get to the bottom of what’s happening to this now-threatened world, and in the

process, fight dragons, fly through the air on mythical creatures, witness the

unimaginable destruction and carnage of war, and discover a great deal about

themselves.

Denial is a coming-of-age story, although I

hesitate to call it a YA book because of the amount of graphic violence and

sexual content. This is not Tolkien or C.S. Lewis; it’s more like Stephen King,

and it might be disturbing to sensitive readers.

The story is

told through four points of view, and the author is rather clever in the way he

subtlety switches some stylistic elements chapter by chapter, depending on what

character we’re following. He could have distinguished the characters even more

if he had written one of them in first person perspective. But that’s a small

matter. The one distinction that isn’t remotely subtle is that Alex’s chapters

are in comics form, which is appropriate considering the character’s age of 13.

Comics are

another thing I avoid, for a similar reason that I avoid fantasy. They take

effort to get through and interpret correctly, to figure out what’s going on in

the scene. The artist has to tell the story clearly with a limited number of

frames, and I would be lying if I said that I could always tell in this book exactly

what I was looking at. But I usually could, and that is a credit both to Strife’s

drawing talent and his ability to tell a story visually.

The

characters are all unique and yet relatable in their own way. As a reader, I

changed my opinion about various characters several times. For instance, I

found Sebastian to be initially self-righteous and arrogant, but he grew on me.

Kaece was not immediately likable, and the author’s decision to always have her

say “ya” instead of “you” is something I found rather distracting, but by the

time I was halfway in, I felt more for her, on an emotional level, than anyone

else in the story. It was the contrast of the tough exterior but vulnerable interior

that make her the most intriguing.

Strangely,

Rebecca and Alex seem under-developed and ordinary by comparison, and not simply

because they are human. Rebecca has all the teenage angst and drama you would

expect, all the emotions running wild in a thousand different directions,

struggling with self-esteem, confusion over sexual identity, and rebellion

against other people’s expectations of her. And her brother, well…He’s simply a

precocious 13-year-old wanting to prove his worth and bravery, but in spite of

his chapters being illustrated, his story is somewhat one-dimensional. Why don’t

these two ever think about their parents, or their home lives? Aren’t they

worried about their families or friends? Aren’t they grieved at the notion of

never being able to return home? Rebecca engages in self-pity over failed past

relationships, but we get no sense of what life had been like for the siblings,

beyond that.

Overall, the

novel is fast-paced, engaging, and unpredictable. As the story unfolded, I

could never tell where it was going, nor what would happen next. There are many

unexpected twists and turns. And it’s a bit of an emotional roller coaster as

well because the stakes are very high for some of these characters, not only in

terms of what may happen to them, but in terms of the revelation of who they

really are, and what that means. Some big questions are asked: Does love

override duty and loyalty? Do ethics matter in wartime? Are there some things that you can’t forgive?

As a gay

guy, I didn’t love the lesbian romance aspect of the story (I’ll always prefer

stories about dudes), but it was very intense and relatable. Rebecca has some

self-loathing that she has to get over, and that’s pretty universal, I think.

Creationists

may take issue with an explanation for Earth’s origin other than the one found

in the Book of Genesis. I know I did, even though you can easily answer by

saying “it’s a fantasy novel, not a theology text”. I don’t know, for some reason

it just nagged at me, probably more than it should, like an itch that you can’t

reach to scratch.

But by and

large, this is a thoughtful work of fantasy fiction, and full of heart, a labor

of love for an author who loves a good story, and who loves the people he’s

telling it to.

Sunday, December 18, 2016

The not-very-prolific work of Scott Heim

Twenty years ago, I had an encounter with an author that changed my life. I was reading a new magazine called XY, which was geared toward young gay men and was full of erotic photos by the likes of Howard Roffman and Steven Underhill. It also had lifestyle and culture articles. One of these articles focused on three authors who wrote sexually provocative material. One of those authors was Scott Heim, and it’s not the text of the article that caused me to read his debut novel, Mysterious Skin, but rather the photo (above) of the author at 29. Someone this lovely on the outside had to possess something equally beautiful on the inside, right?

Over the

next few years, I would become such a fan that I had an ongoing email correspondence

with him, briefly designed and ran his official website (before he needed

something more polished and professional), shared some of my creative writing

with him, and would later direct Prince Gomolvilas’ adaptation of Mysterious

Skin as the first production for my first production company, Book of Dreams.

All of this represents some real emotional highs and lows for me, success and

failure, and eventually culminated in me not really being the fanboy I once

was. Oh well. It was fun while it lasted.

You may know

Mysterious Skin from a 2004 movie with Brady Corbet and Joseph Gordon Levitt.

And for what it’s worth, the movie is—for most intents and purposes—very good.

I have it, and I like to watch it with daring individuals who like gritty and

provocative storytelling. In this way, it represents the novel very well. Of

course, there’s a lot more to the book than “gritty and provocative”. It is

also full of rich imagery and lyrical beauty. It has the raw emotional punch of

ten novels. It’s a rather stunning coming-of-age meditation. It’s a Kansas

travelogue, which actually makes the state seem like someplace you’d want to

visit. All these things I would consider a trademark of the author.

Mysterious

Skin is about two young boys who have essentially the same traumatic experience

(sexual abuse by their little league coach) but interpret it in very different

ways. Brian blocks out the experience completely, and when fragments of memory

start to surface, he believes they are evidence of an alien abduction. Neil, on

the other hand, expands on this intro to the adult world of sex by finding lust

for his mother’s many boyfriends (who each remind him of idealized Coach),

discovering gay porn, and becoming a high school hustler. The novel, in a

nutshell, is about the journeys that both boys take from childhood to early

adulthood, as they discover the true significance and meaning behind what

really happened to them.

Of course, many other interesting

characters are introduced along the way: Brian’s prison-guard mom and college

sister, Deborah; Neil’s overly-carefree mother and fag-hag best friend Wendy;

Eric, the new gay in town who wants a deep connection with Neil, but has to

learn that such a thing does not exist. In the novel, Eric is my favorite

character, while the movie offered a version less than what I imagined. Then

there’s Avalyn, the lonely older woman who Brian reaches out to in his UFO explanation-seeking

after she was on a TV show talking about her own abduction experience. All

these characters are as vivid and bright as the rural Kansas landscape,

eventually juxtaposed with the mean streets and clubs of New York where Neil

realizes he can get more money for sex, but ends up with more than he bargained

for.

The novel has one of the most

brilliant and emotionally satisfying endings I’ve read, even as it leaves you

wishing for more. Mysterious Skin was a huge success in the gay lit market, and

the film was inevitable, despite the challenges of some pretty graphic and

extreme content. What’s more surprising was the play by Gomolvilas, which was

actually written before the film, and is different in many ways. I’ve written

some about my production of the play, so I’m not going to do that here.

Shortly after I read Mysterious

Skin, Scott Heim was at Powell’s doing a tour for his second novel, In Awe. I

brought a friend and showed up in my pin-striped baseball jersey style Foetus

shirt and sat in the front row, being all geeky and trying to think up

not-stupid questions to ask. When I met him and he signed my book, I felt

embarrassed like the geeky fanboy that I was.

I’m not sure why I started writing

to him after that point. Maybe it’s because I was in fact so dissatisfied with the

geeky fanboy meeting. We exchanged several emails before I even finished In

Awe. Part of this is because I’ve never been an avid reader anyway, and his

self-described maximalist style is sometimes challenging for someone who doesn’t

really indulge in a lot of casual reading. He’s very descriptive, and makes the

most of each sentence, each paragraph, and really relying on dialogue as little

as possible. When I finally finished, I remember not having the words to tell

him what the book meant to me. Somehow it overshadowed Mysterious Skin—at least

for me, maybe only for me—and that was no small achievement.

In Awe deals with three social

pariahs living in Lawrence, Kansas. Boris is a teenager who’s obsessed with a

boy at his school named Rex who, unfortunately for Boris, is part of a cadre of

dangerous and malicious country rednecks. Sarah is an adult woman, but doesn’t

adhere to most of the trappings of adulthood, as she hangs out with Boris,

helping him write his prize zombie novel and acting out scenes from horror

movies. The third person in this crew is Harriet, an older woman who lost her

son Marshall to AIDS-related illness. (Marshall used to be part of the gang of

misfits as well.) Soon, strange and

scary incidents start to happen. Acts of horrific violence, coupled with hate

crimes raged against this trios of unlikely friends, propel this suspenseful novel

to a shattering and breath-taking conclusion.

Alas, In Awe is not as easy to

categorize or sum up as Mysterious Skin, nor is it easy for me to explain why

it means so much to me as a pivotal work of influence and inspiration in my own

life. I couldn’t begin to tell you unless you first read it. It will likely

never be filmed, and Scott Heim actually found himself without a publisher in

the wake of this less commercially appealing work, as he was in the process of

writing his third novel.

After I read In Awe, I was compelled

to read his book of poetry, Saved From Drowing, which was actually published

before Mysterious Skin was, but in limited numbers, thus kind of hard to find.

Heim’s poetry is much like his prose. I would say actually that it is exactly

like his prose, but structured into verse form. If you hear it read aloud, you

hear a story, not anything that sounds remotely like verse. And indeed, some of

the poems in the book found their way into his novels, altered in some cases, sometimes

just the central themes remaining. Two of the biggest examples are “Turtle” (which

became an incident in Mysterious Skin) and “Brad, Bottom Drawer” (which

describes an obsessive behavior very much like Boris behaves with Rex in In

Awe). It was a revelation reading these, and seeing how ideas evolve from one

thing to another. It was an interesting peek into the creative process.

It took over a decade for Heim to

finish his third novel, We Disappear. The finished product ended up becoming

his most deeply personal work, as it dealt with depression and the loss of his

mother. It concerns the character of “Scott” who comes home, recovering from a

drug addiction, to care for his dying mom, Donna. From this framework, Heim

adds intrigue reminiscent of his second novel with the discovery of a murdered

teenage boy, and the obsession Scott shares with his mother regarding missing

persons: collecting articles, playing detective, and trying to imagine possible

outcomes.

There is a lot of potential in We

Disappear, but for me, its execution falls short. Maybe it’s because Heim is

torn between telling a fictional story and writing a memoir of his last days

with his mother. There is a shadow of sickness, addiction, depression, and despair

that covers this novel, making it a very difficult read if you’re not on the

right anti-depressant yourself. There are plot points that don’t pay off. There

are questions that don’t get answered…but not in the good way that the first

two novels leave you begging for more. This one just kind of ends, and you’re

relieved for it. At some point, I want to reread this and see if I have a

different reaction. But for now, it’s not a book I recommend.

There is a series of e-books that

Heim has published called The First Time I Heard…, in which he and other

writers describe their experiences first hearing favorite musicians. I haven’t

read any of these, but at least the Kate Bush one is probably fairly

interesting.

So, to sum up, if you have never

read Mysterious Skin or In Awe, and you’re someone who knows what it’s like to

feel like a marginalized person in our society and can relate to material like

this, I say get those books now!

Saturday, December 3, 2016

Comfort and Joy

A few years ago, I was browsing through Samuel French and Dramatists, searching for a Christmas-themed play, particularly a Christmas-themed play with gay characters. One of them I stumbled upon was Comfort and Joy by Jack Heifner. I never actually read it, but I put it on a mental list of plays I might do someday. Fast forward to fall of 2016, and I see that Twilight Theatre Company—arguably the most daring and socially progressive community theatre in the PDX metro—is producing that play. Now, as a rule, when there is a production of one of those plays that I have on the mental list of possibilities, I don’t go see it. The reason being that I don’t want to see someone else’s artistic vision for the piece, and then be unduly influenced by it later. It’s part of how I try to maintain my own greatest level of artistic integrity in my work.

But I made

an exception in this case.

Programs

were not available opening night because of a misunderstanding with their print

shop; this upset me because I feel like that’s part of what you pay for and

what you should get with the price of a ticket. Any theatre unable to provide a

program should offer to mail their patrons one (a real paper one, not the PDF)

at no cost. I have a wonderful box full of 25 years of programs. I always save

them, and they’re one of my favorite things. The reason I bring it up here is

that I won’t be able to name as many names when discussing the play, unless

they are on the Facebook event page; at least the actors are.

Comfort and

Joy takes us back at least 20 years to a time when civil liberties for LGBT

people were not what they are now, and many in the gay community were still

constantly mourning the loss of more and more loved ones by the AIDS epidemic. Its

lovable protagonists, Scott (Andy Roberts, who brought joy to HART audiences

two years ago in White Christmas) and Tony) are a happily

partnered couple, living in a lavish home (not so lavish, actually—more on that

later) in the Hollywood Hills, awaiting the arrival of Scott’s harpy mom, Doris

(Angela Michtom) for Christmas Eve dinner. Problem: relations between mother

and son are already strained, and to add to the festivities, Tony’s obnoxious

siblings, Gina and Victor (Adriana Gantzer and Josiah Green,

respectively) come to call. She’s pregnant and apparently homeless, and he’s

been dumped by his Christian extremist wife, who’s taken off with the kids. To

top off this Christmas tree of chaos is a freakish fairy (David Alan Morrison)

in silver tights, ghastly blue Crocks and a mess of garish makeup and tattered

wings. And yes, the word “fairy” seems to have a double meaning here. He is there

to manipulate the characters and shape the outcome of their lives.

If you

haven’t already guessed it by now, this is a comedy, but it has its dramatic moments

played out with mixed success. I want to single out Morrison’s work as the

Fairy because his job is the most challenging. Throughout the play, there are

numerous flashbacks to scenes from the various other characters’ lives, and

Morrison—as the Fairy—has to occupy all the characters from the past that are

being represented, all of which have a huge impact on who these people are

today and the demons that haunt them. Morrison brings real depth to all of

these characters and showcases an impressive range as an actor. What makes his

job even more challenging is that director Jason A. England was not entirely

successful in making these sudden scene shifts flow in a clear, concise, and

coherent way. The shifts in time were jarring and clunky, causing the audience

to have to pause for a moment to figure out, “Okay, where are we and who are we

talking to?” This, in spite of an ingenious, hilarious, and very timely

lighting design element. (I don’t want to give it away, but this lighting

effect, if used in other future shows, will never be as funny of a joke as it

is right now.)

As I

said before, the two lovers at the center of the story are indeed lovable, and

that wouldn’t be possible without the fine performances of Roberts and Torres.

What’s interesting here is that you never see the full extent of the chemistry

between these men because we’re seeing them on an extraordinarily stressful day

when a thousand things get in the way of that. And yet, there is clear proof

that the chemistry exists. You get a glimpse here and a glimpse there, and you

know from these nuanced performances that these two people have overcome

challenging lives and arrived at the kind of happiness that the rest of their

family has no ability to understand.

As

Dorris, Michtom was appropriately grating, perhaps even a little too much so.

Eventually, we see her humanity, but it takes a little longer than it should.

This is not solely a script problem. A director and actor can find ways to reveal

softness in a character, at least to the audience, if not to the other people

on stage. I found there was a similar problem with sister Gina, even though she

doesn’t show up until the second act. But the most problematic performance for

me was Green’s Victor, who was constantly delivering his lines in a weepy,

drunken slur. I would rather he had burst into full blown tears at various

points instead of that constant vocal affectation.

The

greatest problem I had in terms of the design elements was the set. It had the

look of a very generic box set that could be interchanged with hundreds of

other living rooms in hundreds of other community theatre productions. It was

not remotely evocative of what a Hollywood producer’s residence would be, nor

did the décor really reveal much about who the occupants of this home were. On

the makeup front, the Doris character was supposed to have had a recent

facelift; there seemed to be no effort taken to convey this.

But

plays are about people, not nearly as much as what they wear or the places they

occupy (though those things can be important sometimes). If you care about the

people on stage, then the production is doing its job. Relatives can be

annoying at times, but one of the things the holidays are about is being able

to overlook those faults, forgive, and recognize the things we have in common.

All of the performers in Comfort and Joy were able to conjure moments of

empathy and compassion for their characters, which made up for the other inconsistencies.

Saturday, October 29, 2016

The Best Productions I've Ever Seen

This entry

has been inspired by a recent conversation I had with my theatre coach. What

makes an excellent production? What are the qualities that I will strive to

achieve in my own productions with my theatre company?

I should

qualify the title of this post. I’ve seen many scores of shows in the last 25

years, and most of them had me leaving the theater thinking, “I could have

stayed home and watched TV.” What I really mean by “best” is the impression they

had on me. For instance, the first two shows listed were high school shows…but

they were really my first exposure to the magic of theatre, and by seeing them,

I knew that I wanted a life in theatre. If I saw those same productions today,

would they have the same effect? Maybe not. I want to emphasize that I’m

talking about productions here, and not the plays themselves. I’ve seen

lackluster productions of excellent plays; they are not what this list is

about. And yet…I may contradict myself when talking about some productions I

saw, like Equus, which may not have been an ideal production, but the fact that

it introduced me to an amazing play is what made the powerful impression.

Finally, I should note that while I’ve seen many, many shows, I don’t see as

much as a lot of people who work in theatre, locally. Mainly, I just don’t have

the money to go to many shows, and ushering has never appealed to me. So

obviously, there is a lot of great stuff out there that I have missed. I would

welcome in the comments section anyone who wants to share the best show they’ve

seen. Oh, one final note: to appear humble, I am not including shows I’ve

directed!

Little Shop of Horrors – OCHS, 1991

A lot of

people might miss all the layers in this sci-fi/horror/comedy/musical. We’re

dealing with poverty, domestic abuse, being an outsider, the dangers of

ambition, and the question of how far you’ll go to protect the ones you love,

or to hold onto a dream. Add to all that an excellent playlist of songs, and

this is really a powerful play when done right.

The Foreigner – OCHS, 1991

Shout-out to

my high school drama teacher Karlyn Love, who inspired me greatly and is

probably incapable of doing a bad production, at least as far as high school

plays go.

Waiting for Godot – Lewis & Clark, 1993

This and the

next play on the list were my introduction to “theatre of the absurd”. The

floor of the stage was a Salvador Dali soft (or melting) clock, and that’s one

of the most inspired scenic design choices I’ve ever seen.

The Birthday Party – 1993

This was

performed at IFCC, but I don’t remember the company that put it on. Strangely,

my biggest takeaway from this play is a question from the interrogation scene: “Is

the number 846 necessary or possible?” Now, please, dramaturgs, explain the

significance of that to me, or don’t because it’s really a very delightful

mystery.

Jeffrey – Triangle Productions, 1994

The first “gay

play” I ever saw. I had an instant crush on its star, Robert Buckmaster, who

passed away very shortly after. What made his performance so good was the depth

of his honesty and tenderness with which he shared the heart of his character

with the audience. (See note on Dog Sees God later in post.)

Equus – Paula Productions, 1995

Dysart was

not well cast, and for some reason, the director (or the producer, who I would

later become very acquainted with doing my own shows there) decided not to have

the nudity in this production. I don’t agree with the decision and it’s not how

I would do it, but it’s important for me to say that the piece was still very

impactful without it.

The Lady From Dubuque – CCC, 1996

This production

was absolutely fierce, and the mystery of the title character brought chills

and practically took my breath away.

Suicide in B Flat – Liminal, 1997

Like an

episode of The Twilight Zone (but then again, aren’t all Sam Shepard pieces

like that?), with bits of music thrown in. I had no idea what was going on or

why it mattered, but I didn’t care.

The Seagull –

Paula Productions, 1999

Paula

Productions existed for many years. It was a one-man operation, and the venues

it occupied were tiny living room sized spaces. The plays were largely panned

by critics, especially Stefan Silvis, who wrote for Willamette Week at the

time. But this resonated with me. Its star, Myron Chase was a loose cannon,

very unpredictable, sometimes doing his own thing instead of what was

rehearsed, forcing his fellow actors to improvise. But he had a raw talent and

magnetic appeal, and I really found myself feeling empathy for his Kostya.

Peer Gynt –

Paula Productions, 1999

My friend

Dan directed this in the afore-mentioned tiny living room size space. If you

know anything about this play, you know it’s a sprawling epic with multiple

locations, even more characters, and it’s a challenge to stage anywhere, much

less a tiny venue like the Jack Oakes Theatre. With precision use of costuming,

lighting, and sound, plus top notch actors, it worked, and it showed me that

something I might have thought impossible was possible.

The Velocity of Gary (Not His Real Name) – Triangle Production, 2000

Danny

Pintauro in a touring one-man show about a gay hustler. And like most Triangle

shows at the time, featuring full male nudity. But that’s not what made it

good. (Yeah, some of you think you know me so well!) One-man shows are hard to

do. They are hard to watch. It’s like listening to an audio book. Your mind can

wander. That did not happen here. (See note on Howie the Rookie.)

Cabaret – Best of Broadway, 2000

Just an

awesome spectacle, and there was nothing about it that was not totally amazing

and inspiring. But the ending…the quintessential “kick in the gut”…so affecting,

so breathtaking, hands down the most chilling moment of theatre I’ve ever

witnessed.

Lion in the

Streets – Theatre Vertigo, 2000

I wish I

remembered more about this amazing piece of theatre, but 16 years will do that

to you. Mainly I just remember it was earth-shaking and brilliant.

After the Zipper – Stark Raving Theatre, 2002

Matthew

Zrebski is one of the most brilliant playwrights around, and this gave me

chills. And he’s local! Lucky us. I saw it twice, which is unusual.

Dog Sees God

– CoHo Theatre, 2009

Two things

that made this show great: the earnest performance of Noah Goldenberg (see note

on Jeffrey), and a moving and brilliant visual in the very end of the play,

which I don’t know is from the playwright or director Brian Allard, but the

image stayed with me for a very long time.

Over the

River & Through the Woods – Magenta Theatre, 2011

So I gotta

be honest about my reason for loving this production of the popular community

theatre staple (I mean really, this play is as ubiquitous as Rocky Horror). My

dad gave his best performance not directed by me as a family patriarch

struggling with life’s hard transitions. I’ve worked with my dad many times,

and it would be easy to accuse me of nepotism, but if you saw this (which I had

nothing to do with), you know that he’s an actor of great depth and

versatility.

Vincent

River – Sowelu, 2012

Playwright

Philip Ridley, director Barry Hunt, two extraordinary actors in a play dealing

with grief and hate crimes. This was so beautifully produced and performed, I

wish I had a recording of it to watch over and over again.

Rope – Bag &

Baggage, 2015

There was a

lot that was great about this production, but Michael Teufel as the conscience

of the piece was the stand-out. If I ran the Drammy committee, he would get the

award for best actor.

Howie the Rookie – The Factory Theatre, 2016

One man

shows are hard. (See note on The Velocity of Gary…) Especially with a thick

Irish accent and a performing space the size of a bathroom. Nevan Richard was

amazing here.

At some

point after this blog is posted, I will remember one that I’ve forgotten to

include, and probably be very frustrated. So maybe check back for updates?

Monday, September 5, 2016

American Crime, season 1

Months ago,

I could not stop raving about a show nobody seemed to be familiar with (because

it wasn’t on cable), American Crime, specifically season 2. (American Crime is

a show with a partially recurring, or “repertory”, cast, but playing different

characters in a new storyline each season.) I tried to get everyone to watch it,

and basically said it was the best thing I’d ever seen. As far as I know, no

one has taken my advice so far. But now that both seasons are on Netflix, not

only do YOU have a chance to watch the show, but I also was given a chance to

catch season 1, which I had not seen. Obviously, the big question on my mind

was, could season 1 be just as amazing and brilliant as season 2 was? Well, I’ll

save you the suspense. The short answer is no.

It’s kind of

the opposite of how things usually go. People blow their best load on their

first effort, and then go into what’s commonly referred to as the “sophomore slump”.

In my view, the paradigm that fits this situation is that season 1 was a

practice run for the real test of greatness that was season 2.

The biggest

problem I had with season 1 is that if you’re not a petty criminal, violent

thug, drug dealer, addict, racist bigot, or juvenile delinquent, there were not

very many characters to identify with, and though there were multiple

interlaced stories throughout, it was hard to care about the outcomes because

the people were so inaccessible. As a writing student (perpetually, it would

seem), I’m told that I must love my characters because the audience must love

them. Series creator John Ridley seemed to have gotten the memo for season 2,

but not for season 1. There were exactly two characters in the whole series

that I had consistent and genuine compassion for. One was a grieving father,

played by Timothy Hutton, whose son had been murdered, and who is trying to reconnect

with a family that refuses to forgive him for his shortcomings nearly 20 years

earlier. The other is also a father, a Hispanic auto shop owner (Benito

Martinez) whose son has fallen in with a bad crowd and who is desperate to save

his family.

Everyone

else is so consumed with one obsession or another--passions and prejudices,

vices and vendettas--that it’s impossible to root for them. At one point, a

young woman overdosed on drugs, and I was actually happy that she was dead

because her character was so annoying. (To my disappointment, she actually

survived the overdose.)

Not that the

actors aren’t doing their jobs, and remarkably well. Regina King got an Emmy as

a Muslim woman on a crusade to rescue her brother from both a murder rap and a

really horrible girlfriend (see last paragraph). Felicity Huffman is in danger

of being typecast in the same series because while her characters in each

season are quite different, they are both cold and rather unsympathetic. One

hopes she will get a warmer character in season 3. Hutton is wonderful and

heartbreaking.

This show

tends to run the gamut of nearly every social issue you can think of. It’s like

writing down all of society’s ills on pieces of paper, putting them into a hat,

and mixing them up. Then showrunner Ridley pulls out 10 pieces of paper from

the hat, and blends them all into a volatile tapestry that is the story for a

season. Season 1 deals with racism against blacks, Hispanics, and whites (yes,

I said whites too). It deals with different religions (in this case, Islam and

Christianity), and how people of different faiths may approach things differently,

but also the same. It deals with drug addiction, immigration issues, gang

violence, and even touches briefly on military impropriety.

And yet, one of the

things that makes this show successful is that it manages to highlight these

issues without being preachy. The way they do this is to focus on the

characters and their stories, which are very believable, even if you don’t get

invested in the people because they’re assholes.

[Pseudo-spoiler

alert:]

Part of my

problem with not liking most of the characters had to do with my own Christian

faith, as much as any kind of open-mindedness required of me as a creative, and

storyteller. It was disturbing to realize that I rather liked the idea of some

of these characters’ suffering. While lamenting how tragic it was that one

character (Hutton’s) could not be forgiven no matter how hard he tried to make

amends, I found myself not very forgiving of much of the behavior that I saw

played out in front of me. “They will deserve what they get,” I found myself saying.

But of course, my heart softened as each situation was brought to its

resolution, and one character--a young fiancé of Hutton’s surviving son--expresses

what I believe to be the heart of the story, a call for love and compassion.

But it comes too late for some. And that just pisses me off.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)