Friday, October 13, 2017

Walking Out (2017)

Under the big sky of Montana, a father and son walk across some of the most beautiful terrain on God's Earth. Towering snow-capped mountains, barren winter trees, rivers that seem like they are the most clear, clean and pure anywhere. But the land is as dangerous as it is beautiful, as are the creatures with whom our strong-yet-frail protagonists share it.

Here is another wilderness survival story that might remind you of either Jack London or Grizzly Adams, depending on your level of tolerance for vicariously roughing it. Its stars are Matt Bomer and Josh Wiggins, two actors who are as good looking as the scenery, which is unusual for this type of film. And yet, somehow they seem to belong, in the same way that the slick photography seems fit for a Montana tour video or a prize-winning feature in National Geographic. From the first frame to the last, it is a feast for the eyes. All of this lures the viewer in, like a hunter's bait, making you feel at ease, even though you know there are tough times ahead.

Cal (Bomer) is a life-long mountin man. His father (Bill Pullman) was a mountain man. His father's father was probably also a mountain man. Cal's son, David (Wiggins)...not so much. He lives with his mother in Texas and sees his father about once a year. Every year he goes up and experiences a taste of what his father calls heaven. He learns some hunting and survival tips, bird calls, etc. Then he goes home and forgets what he leaned. But this time will be differet, his father determines. "This year, you make your first kill."

Initially, David is a little bit like I think I would be in that situation: homesick, out of my element, glued to my phone. There are moments of disconnect and awkwardness between father and son, but not as many as you might expect. What's very clear from the onset is that these two love each other, in spite of their differences, and they're not out to make each other miserable. Cal has a deep desire to share his heritage with his son. And unlike most movie teens, David doesn't take until the film's end to realize and appreciate the importance of this, and he soon comes aboard his dad's plan, wanting to please him.

Once the two commit to this adventure, tensions seem to lift, and they enjoy some thoughtful, sometimes funny, father/son time. Cal tells David about his own father, and the important lesson he learned in his first big hunt. In the shelter of a sheepman's hut one night, the boy has a startling moment of introspective uncertainty when his dad looks him in the eyes and asks him what he really knows about life. This further propels David's desire to learn from his old man so that he may have something to pass on to another generation.

In daylight, hunting begins in earnest, and adventure leads to misadventure. Cal gets critically injured and David must use all his strength and what he has learned to get his father out and save both of their lives. Here is where you might expect to see some of the familiar survival movie tropes that you've seen before, and you kind of do, except that it's somehow...different. The stakes have never felt this high in other movies, and yet there is a calm and measured determination with which these two men (because yes, the boy is quickly becoming a man now) deal with this life-or-death struggle. And as the two slowly--ever so painfully slowly (for them, not the audience)--make their way toward rescue, there is a true bonding between father and son that never would have happened if this crisis had not fallen upon them. From now on, their lives and their relationship are changed forever.

I watched this film with my dad, and it was impossible not to think of our own relationship while watching this film. I thought of the things we have in common, and the things we don't. I thought about times of closeness and other times of distance. But mostly, I thought about the unconditional bond of love between fathers and sons, between family members. I realized that not eveyone is blessed with this, and I felt grateful.

Walking Out was filmed entirely in Montana by Montana natives Alex and Andrew Smith, based on a much beloved story by David Quammen, with amazing cinematography by Todd McMullen. Point of trivia: Wiggins knew that his character would have to carry Bomer's character on his back for much of the film. He thought there would be a dummy, but there wasn't. The young actor is stronger than he looks.

This poignant film is available is select theatres (possibly not ever Portland) and VOD. Thank heaven for VOD.

Tuesday, May 9, 2017

American Crime season 3

The key to

handling disappointment is managing expectations. Nobody gets it right all the

time. I was so in love with the previous season of John Ridley’s Emmy-winning

series that I assumed I’d be in for a real treat with season 3. But while there

is some merit (it would be hard for Ridley to completely misfire), the season

is kind of a mess, and not even a hot one, but rather lukewarm.

The third

season takes on abuse and exploitation in its many forms. We have migrant

workers on a tomato farm who have to live a dozen people to a trailer, an

environment rife with peril. They don’t get paid enough to ever move on because

they have to pay for their lavish accommodations, food, and “health care”

(sometimes illegal drugs) out of their low wages. Oh, they’re also beaten,

overworked, raped, and worse. Being a migrant worker is no picnic. Take that,

Mr. President.

The tomato

farm featured here has been run by an old man who is now on his death bed. It

has been taken over by his oldest daughter, a mean-spirited, manipulative

control freak, completely devoid of empathy. When the wife of one of the farm

owners, Jeanette (perennial favorite Felicity Huffman), starts to ask questions

about the welfare of the workers, she is utterly dismissed and made to feel

worthless.

I mentioned

drugs before. Several characters,

including Coy, played by last season’s Connor Jessup, are addicted, and this

addiction is used as a means of control. (And boy, did I want to see more of

Jessup in this, but he was really a more supporting actor here.)

Another form

of exploitation is human trafficking and prostitution. Dedicated and caring

social worker Kimara (played by Regina King, who won Emmys the last two years

for her roles on American Crime) tries very hard to get young men and women out

of this lifestyle before they end up dead or in jail, but for her, it’s always

two steps forward, one step back. On top of that, she is having fertility

treatments to have that baby she’s always wanted. This probably explains her

motherly instinct. She is certainly the most likable character in the show this

season.

Then there

is the French Haitian nanny, Gabriella—played with heartbreaking brilliance by

newcomer Mickaelle Bizet—who was brought to America by an extremely unhappy

couple (Lili Taylor and Timothy Hutton) to watch their son and to be abused. Taylor’s

character is very enigmatic…probably too much so…and Hutton’s character is

simply monstrous.

Most of

these stories are snapshots with little air time. Much is hidden in terms of

what actually happens, with whom, and why. There doesn’t seem to be much reason

for this. A sense of mystery? I call it a sense of confusion. The season is

only 8 episodes long instead of 10 or 11, like before. Thus, there is little

time for story and character development. Every story feels disjointed, in

spite of the fact that there is a loose thread running through each. The story

of the migrants only takes up the first 4 episodes, while the nanny’s story

picks up in its absence for the second half. We get Kimara’s and Jeanette’s

stories through all 8 episodes, perhaps because of the popularity of the two

actresses, but only Kimara’s story is engaging to watch. Jeanette is a doormat

who tries for about a second to become an independent woman, but ends up caving

in the end.

Perhaps the

most emotional story is that of Luis Salazar, played by Benito Martinez, a Latin

American immigrant who has come to look for his missing son. When that story is

resolved in what is really the most intense moment in the series during episode

4, everything that comes after is anticlimactic.

This season’s

themes are overtly political. This is a contrast to what has come before in the

series. Instead of telling a gripping story with amazing, relatable characters

and letting the audience make up its own mind, the producers have taken it upon

themselves to educate the privileged white patriarchy. In doing so, they have

reduced the show from something exceptional to something common.

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

13 Reasons Why (or 13 Exercises in Guilt)

I don’t

often get people wanting to share and discuss pieces of drama with me. That’s

actually one of my great Life Disappointments. There are things I have a

passion for, but few people in my life—if any—tend to share those passions. (For

those who failed to jump on my American

Crime train, you’re vindicated somewhat; season 3 was a complete disaster.)

Then once in a blue moon, people see something and it reminds them of me, and

they want to have that mutual catharsis. It’s so rare that I can’t turn it

down. Several people came to me about 13 Reasons Why, and even my great-niece

seemed interested in seeing what I thought, which was kind of cool. So here we

go.

When I

entered film school back in 2006, one of the first things that came out of a

teacher’s mouth to her students was, “Don’t do any projects about the topic of

suicide.” I was taken aback by this because it seemed insensitive to ban a

subject that so many people care so much about. No explanation was given that I

can recall, but with further reflection, I realized a possibility. The sad

truth is, it’s not uncommon for young people to think about suicide. There are

varying degrees of severity, from philosophical contemplation to thoughtful

ideation to actual intent. But I think it’s safe to say that this topic is a

road well traveled by teens and young adults. So it’s hard to add anything new

and meaningful to the discourse. If you don’t do it well, you subject yourself

to harsh criticism, even mockery by people who question your sincerity. I had

an awful experience in one of my scriptwriting classes in which I did write

about The Forbidden Topic after someone I knew from work killed himself. I was

struggling to find ways to deal with it, and trying to use my writing to help.

But when it was read in class, it was laughed at and completely misunderstood,

bitterly reminding me of that first rule that I heard on my first day of

classes. Now I think the prohibition (or maybe that’s too strong a word, maybe

“discouragement” is better) of the subject was because the school didn’t want

to deal with any complicated situations that might arise from a student using

their creative skills to cry out for help. Students are just cash machines to

these schools.

Of course

there have been some good films made about suicide. One is Permanent Record

(1988), one of Keanu Reeves’ first efforts. Prayers for Bobby (2009) is a good

one as it relates to a Christian teen trying to reconcile his faith with his

homosexuality. Oh, and it’s a true story. It’s got Sigourney Weaver, so you

should check it out if you haven’t. There are also bad movies about suicide.

Heathers turns the whole thing into a rather tasteless joke (and people don’t

get why I don’t like it.) But there isn’t a lot out there that really addresses

this can of worms in a way that is not perfunctory and superficial.

The best

thing about 13 Reasons Why is that it’s got the balls to tackle what is

actually a difficult subject in a very thoughtful and provocative way. It asks

tough questions and forces the viewer to engage with its subject matter and

draw their own conclusions. It is flawed, and I’ll get to that in a bit, but I

do feel that the producers of this show have tried to do something positive for

humanity; it’s not just another cynical exploitation of our culture’s current

biggest cash cow, the Young Adult market. They try hard to get it right, and

they do not succeed in every aspect, but they do succeed in some.

The acting

is top notch. This is really the next generation of great actors that we’ll be

seeing a lot of in the future. There are many key players, but two primary ones

are the central focus: Hannah (Katherine Langford), the girl who killed herself

but not without making 13 tapes explaining her reasoning and who she blames for

her fate, and Clay (Dylan Minnette, who was also a “Clay” many years ago in

Holly Hunter’s crime series, Saving Grace; I was shocked when I learned that

this was the same actor, all grown up), the unfortunate current recipient of

the tapes, more tortured by them than anyone else because he actually cared for

Hannah. Langford does exactly what she’s supposed to do: create a lovely and

lovable character whose suicide stabs at the heart of viewers who can’t help

but feel sympathy for such a sweet, funny, sassy, sexy, smart girl whose life

ended too soon. But Minnette really carries the show as he goes through almost

every human emotion on the map trying to find answers and cope with something

that makes absolutely no sense to him. As he gradually discovers the answers,

his character evolves in some really interesting ways. And, in fact, that’s

true about most of the subjects on Hannah’s tapes. Most of them experience a

significant change in their understanding of who they are and how they see the

world. And I do think that’s one of the strongest points the show makes. I also

want to single out Brandon Flynn, who plays Justin Foley, the caddy jock and arguably

the (still living) character who changes the most by the end of the series.

It’s

interesting to observe the multicultural diversity in the cast. You’ve got

blacks, whites, Asians, Hispanics, gays, lesbians, bisexuals, rich kids, poor

kids, kids with cops as parents. You even have a pair of gay dads! But

strangely, there doesn’t seem to be any tension based on these matters, with

the exception of one closeted lesbian (whose reason for needing to stay in the

closet seems really odd to me). It almost seems like the producers tried too

hard to create a homogenized world where these differences no longer separate

people, in order to put a more narrow focus on generalized bullying. But I’m

not sure how accurate it represents your average suburban high school.

Interesting point of fact: none of them seem to have much of a spiritual life.

Hmm…Maybe that’s part of their problem. They don’t believe in anything.

One thing

that happens to me, as a writer and producer of drama, is that when I watch a

show, I’m always scrutinizing the difference between what a character feels or

says, and what I think the show’s creators are trying to say. I am keenly aware

of how one or more characters can become a mouthpiece for a writer to say what

they want about the world or any general subject. The risk here is becoming

pedantic. (If you read Dean Koontz, you know all about this!) As a writer, you really don’t want to be that

obvious about what your personal take is, unless you’re just an unabashed

agenda writer and don’t care that people know that. If you’re wanting to make a

point, but end up sounding preachy, you’re doing it wrong. And there are things

that characters say in 13 Reasons that sound an awful lot to me like a writer

on a soapbox. As the kids like to say, “Fail!” Or “Sad!” (And John Ridley, you

should have read this before conceptualizing season 3 of American Crime; you’ll

get your review later!)

[SPOILERS

AHEAD]

The worst

example of this is variations of a mantra that you hear many, many times in the

13 episodes: “We all killed Hannah Baker.” Well, I’m sorry, but that’s

bullshit. Hannah Baker killed Hannah Baker. And she can blame whomever she

wants, but we’re all singularly responsible for our own actions. Hannah is, as

I’ve already stated, a very likable and sympathetic character, but her final

action before she died was one of tremendous cruelty. She singled out a group

of people, all of whom caused her pain in one way or another—as human beings

tend to do—and proceeded to accuse each of them for taking part in her

motivation to kill herself. And she made each person listen to each story,

causing a gossip storm that nearly ruined a lot of lives. Strange and unlikely

alliances were formed, conspiracies were made to silence those who might become

a threat if word got out, and general mayhem ensued. In the end, Hannah was

exceedingly selfish and irresponsible. And not because she killed herself;

there are many who demonize people who commit suicide, calling them cowards,

etc., and I think as a society we need to be careful about those types of

judgements because they do more harm than good. My issue with Hannah is that

she’s trying to take everyone down with her, and many of those people are just

as fragile and vulnerable as she is.

Some of the

people on her tapes did very minor things. Some did horrible damage. But she

lumped them all together. The only one she inflicted punitive damage on

(encouraging everyone to throw rocks in his window) was nerdy yearbook

photographer Tyler (Devin Druid…is that an awesome name or what?) who himself was

a social outcast and a pariah, about the only male cast member not fit to be an

Abercrombie and Fitch model, sad and lonely and pathetic. Surely there were

others who were more deserving of that kind of treatment. I’m not trying to

excuse Tyler’s actions. But messed up people do messed up things. You can call

him a creep, but ask yourself how he got this way. This kid was bullied more

than Hannah was, and it’s really no surprise to see his arsenal in the last

episode; if there’s a second season, will it be about why Tyler became a school

shooter?

One of the

most enigmatic characters in the show is…oh, I’m not even sure how to label him…hipster Alex, played by Miles Heizer. And I’m honestly not sure

if it’s the character himself who doesn’t know who the heck he is, or if it’s

flawed, lazy writing. He’s one of the most inconsistent, schizophrenic

characters I’ve ever seen on TV. There’s a Cyndi Lauper song I’m reminded of:

“You don’t know where you belong / you should be more careful / as you follow

blindly along / to find something to swear to / you don’t know what’s right

from wrong / you just need to belong somehow.” Of course, that song can apply

to 95% of high school kids, you could argue, but still…I feel like the writers

just didn’t know how to define this character. And though he did the least

amount of harm, he ended up with a self-inflicted bullet in the head, and I

could add, “…thanks to Hannah’s revenge drama”, but then I would be

contradicting my whole judgement of this series.

It’s all a blame game, and the people who

don’t fall for it are the “assholes” in the show, while those that do are the

ones we like. Poor Clay falls hook, line, and sinker for the whole guilt trip,

even though he did nothing wrong. The takeaway from his hearing his own tape is

that he should have stayed when she told him to go. So let me get this

straight: a woman saying “no” doesn’t

really mean “no”? Amid two rape cases,

that’s a strange message to send. Talk about toying with someone’s mind. In essence,

she’s telling Clay that if he had been able to read her mind, she might still

be alive. Gee, thanks. Now I’ve got another 60 to 70 years to try to live that

down.

So the point

the writers want to make: we have to

be kind to each other, and very careful with our words and actions because what

we do and say can have unexpected and devastating consequences. That’s

great; I’m totally down with that message. But the whole “You’re the reason I

killed myself” thing? They could have

done better. But then, I guess that would ruin the whole premise of the show.

Another

issue I have with the show—and perhaps it’s a societal thing as well—is the

“cool parents” phenomenon. You know, don’t pry, respect privacy 100%, don’t

demand answers, don’t discipline, let them learn everything on their own, don’t

try to protect them, let them be smart asses and shut you out, etc. This is not

good parenting. There’s a reason why one of the Ten Commandments is “Honor thy

Father and thy Mother.” Because, often, they do know more than you, and they

can help you. Sure, some kids (like Justin) get bad parents. But Hannah’s and

Clay’s parents were caring and well-intentioned. (I liked the dads more than

the moms, for whatever that’s worth.) But they were impotent and ineffectual. I

was encouraged by Clay’s eventual promise to spill everything to his mom, but I

was disappointed that I didn’t get to see that moment in the show. After all the

evasiveness that came before, I longed for a moment of real connection between

mother and son, but we didn’t get it. I hate how modern teen stories are a

deconstruction (and some might argue, a devaluing) of Family as an essential

institution.

High school

is a brutal and confusing time. Most people are generally messed up,

emotionally. Rapid changes and adjustments are constantly being confronted.

Some people are better at handling it than others. My own experience was a

nightmare, though for me, it was mostly junior high and not high school. In

high school, I was mainly a loner, completely invisible. In junior high, I was

#1 pariah. I was talking to a friend about this show the other day, and he

said, “The bullying I went through was much worse than anything that happened

to Hannah.” And I would actually say the same thing about myself, with the

possible exception of the rape. I would suggest, though, that there is more

than one type of rape. I would never want to minimize the trauma of those who

have been violated sexually, but there are other types of violations that I

would say are just as bad and can affect someone for life.

The sad

reality is that most people are selfish by nature. And the even more sad

reality is that when you’re suffering and try to cry for help, most people

don’t have a clue how to handle it, so they do nothing. People cry for help all

the time, and almost always get ignored. That’s a fact. That’s my own personal

experience talking. It’s easy to give up on humanity and start to believe that

nobody gives a fuck about you. 13 Reasons Why is an earnest attempt to address

these issues, to start a conversation that could lead to some kind of change.

And I have to say it was riveting to watch. For all its problems, I enjoyed it

and was genuinely moved by it.

The show has

not been without controversy. Some mental health experts have suggested that

the show glamorizes—or worse, may inadvertently encourage—suicide. I feel it’s

in the eye of the beholder. I’ve heard that certain acts of random violence may

have the contributing factor of their perpetrator seeing similar stories on the

news and becoming emboldened. But that instinct or drive to violence was likely

already there. Whether or not the news story was the tipping point, we may

never know. And the same is true here. 13 Reasons Why might resonate with a

certain type of personality who is looking for a flashy way to end it and give

all the people they’re mad at the middle finger at the same time, but those

feelings were likely not caused by the show. Art imitates reality more than the

other way around. So you can’t blame a TV show for a tragedy any more than Hannah

could justifiably blame her classmates for an action that was solely her

decision to make. As an artist, I do feel a responsibility to create content

that does not harm, but at the end of the day, it’s not something I have

control over. I do admire the producers of this show for asking the questions,

though I don’t necessarily agree with some of the conclusions they might want

their audience to arrive at.

I will close

this essay with an equation that has been used by many a self-help guru, though

I’m not sure who first coined it: E + R = O. Which simply means “Event +

Response = Outcome.” Shit happens. But no matter how hard we have it, we all

have a choice in how to respond to it. And there is always a response that is

born of grace and leads to healing and hope, light and life.

Friday, February 17, 2017

The Pillowman

As I have probably mentioned, I don't see many live shows, nor do I often go to theaters to see new movies. I simply don't make enough money to afford the luxury, so I must be extremely selective. This means that I often miss shows that my friends are doing, which is regrettable as I know that disappointed feeling I get when my people don't come to my own shows. I say all this to say that Life in Arts' Production of Martin McDonagh's The Pillowman is that rare gem that almost perfectly meets the criteria of my meager budget, and I have no regrets on seeing it, financial or otherwise (although I do have a friend who regrets not noticing that a student discount was available).

The Pillowman is set in what the Dramatists publishers describe as "an unnamed totalitarian state." Now, normally I reserve my negative comments for the end of a review, but I have to structure things differently, because the problems come up right away. When you, the audience member--part of a group that is potentially as diverse as our nation itself--walks into the Headwaters lobby, you see a sign by the concession stand that proclaims, "No Ban! No wall!" In the weeks prior to the opening of The Pillowman, the company--along with many other theatres across the country--participated in something called The Ghostlight Project, which was a solidarity movement among theatre artists to be a source of "light for the dark times ahead." You know, the dark times that will inevitably be brought on by our new President. Director Jamie Rea put her political cards right on the table in her program notes, essentially suggesting that since the election of Donald J. Trump, we now live in such an "absurd Kaftaesque totalitarian dictatorship". According to the program (but not the play itself), this piece is set right here and now. And if, dear audience, you did not pick up on this subtle message, you are provided with a picture of the President himself right there on the wall of the set. At the time of this production, President Trump has been in office less than a month. Such politicization and pandering is unnecessary, distracting and, frankly, beneath the otherwise excellent work by this company. Instead of just presenting a play and allowing the audience to draw its own conclusions, the audience is getting a personal, partisan agenda from the theatre company and being told what to think, which--in a manner I suppose is completely unintentional to the artists--goes right along with the play's themes.

In a way, the totalitarian theme is a bit of a red herring, a plot point that doesn't seem to really go anywhere. This is not the fault of the production, but possibly a flaw in McDonagh's play itself. I am probably wrong; it just seems to me that it's explored a tiny bit and then fizzles out after the first act. Unless you're just talking about police brutality and lack of due process, which is something that has unfortunately existed in every government throughout time. None of that is earth-shattering.

This is the story of two brothers who are accused of murdering three local children. They are locked up and interrogated by a couple of heavies (Bobby Bermea and Jonah Weston) who seem to feel that a person is guilty until proven innocent, and even then, perhaps still guilty under their law. The brothers are Katurian (Benjamin Philip), a writer of dark fables involving children, and Michal (Gary Strong), a mentally disabled man, a year older. The reason the two are suspected of the killings is because they closely mirror the short stories of Katurian. In fact, the stories seem to serve as an inspiration and blueprint for the violence.

To reveal much more of the plot would be a great disservice to the audience. The brothers have a horrific background, a childhood that no doubt inspired the dark writings of the protagonist. The play explores how we are shaped by the experiences of our childhoods and--in light of that--how much responsibility we bear for our actions as grown-ups. It also explores the nature of the creative mind, how an artist is defined by the work that they create, and how closely artists guard and protect their work as sacred. (I can relate to this a great deal.) And, to go even deeper, it asks if an artist (in this case a writer) has any responsibility to his/her audience in regard to content and the possible reaction to it. I was reminded of the story of a school shooting that led Stephen King to take his book, Rage, off the market when the book was discovered in the shooter's locker.

If I could think of one word to describe the acting performances in this piece, it would be "brave". Not only are they dealing with one of the most disturbing topics is existence--the brutal killing of children--but they do it in a very straightforward way, never flinching (unless of course it's natural for the character to do so), and you've got actual children on stage acting this stuff out. I feel this play would disturb the sensibilities of many parents. But McDonagh is a writer who goes for the jugular (so to speak), and in order for a production to work, the acting ensemble must be willing to do the same, and every single one was up to the task.

I did kind of wonder about the character of Michal, who seemed to shift in his levels of maturity and understanding. Sometimes he seemed to have the IQ of a toddler, and other times he was surprisingly astute. It seems like a mild inconsistency, but I'm not prepared to call anyone out on it, because it may be quite intentional. It's the type of thing I'd have to examine with repeated viewings, which, of course, is not possible.

There is a lot that could be said about the original music, sound design, lighting design, set design, props, staging, costumes, makeup, etc. Look, this is top notch work, and I was impressed enough to even be a little envious of what this crew has pulled off. All the different elements work so well together and add to the overall tone of menace and dread. The night I saw it, there were some timing issues with the sound cues, but from a design standpoint, it was absolutely amazing, and I loved virtually everything about it.

I should note, for anyone who worries the play might be too dark, there is actually a lot humor in it. Humor is an absolutely essential element in a play of this nature; otherwise audiences might indeed lack the stamina to endure such a long and deep reflection on human nature's darkest corners.

The Pillowman runs through February 25th, Thursday through Sunday at 7:30 at the Headwaters, 55 NE Farragut St. Ste 9 in Portland. Tickets: https://squareup.com/store/life-in-arts-productions.

Sunday, January 22, 2017

The Falls Trilogy

As a gay

Christian artist, I have spent over 20 years exploring the relationship between

spirituality and sexuality, and the various conflicts and struggles that exist,

of which it seems not that many people are fully aware, even now. It’s a web of complex

issues that is not strictly black and white. Many people, of faith and not of

faith, believe that you have to choose one or the other, and do not understand

the challenges faced by those who refuse to accept that mandate. When I first

saw The Falls, and as I’ve followed the trilogy to its conclusion, I had a

mixed emotional reaction to it. On one hand, I have felt jealous and frustrated

that someone else has, in a sense, beat me to the punch in dealing with these

issues in an extremely effective and satisfying way. Why could it not have been

me? (The answer has to do with my lack of professional connections, confidence,

giving up too quickly, etc.) But on the other hand, I am awestruck and inspired

by this series of films that I truly believe everyone should see because they

are some of the finest and most important works ever made on these topics. Many

have tried before, and have fallen short. I won’t leave you in suspense. This is

a most positive review. I will talk about why these movies work so well, and

include some personal stories along with it.

Note: There

will likely be some mild spoilers here, but nothing that would really ruin the

enjoyment for people who haven’t seen the films. Just be warned though. I want

people to see these movies, so if you think you shouldn’t find out a little

ahead of time, see them first, then come back.

The Falls (2012)

When I saw

The Falls for the first time, I didn’t realize that it was filmed in Portland

until I saw local actor Brian Allard about a third of the way into the film.

Later on, I would see Harold Phillips, who I know from way back when I stage

managed a production of Speed the Plow that he starred in back in 2000. When

you realize that something was done in your back yard and you didn’t know about

it, you have kind of an “aw shit” moment, like, “I wish I could have been

involved in this”, but truthfully I’ve never been involved in film, only

theatre (though I write screenplays). Some of my readers know I went to film

school and it did not agree with me. At all.

The Falls

tells the story of two young Mormon men beginning their obligatory 2-year

missionary work. Apparently, they are paired up (they are called each other’s "missionary companions") and end up rooming together, dorm-style. They receive training

and practice in the evangelistic work that they will be doing.

Not

surprisingly to anyone watching this movie, but surprising to the characters

themselves, the two men (Chris, played by Ben Farmer) and RJ (played by Nick Ferrucci)

form a very strong attraction and subsequent bond with each other, which leads

to sexual intimacy. And not surprisingly, it turns their world upside down

because not only do they have to wrestle with their own internal conflicts, but

they also have a huge secret they must keep.

This film

provides an interesting primer for people who are completely ignorant about the

LDS church and what they believe. We see Chris and RJ talking to so-called “investigators”

who are curious and sometimes skeptical, even critical, about their beliefs. We

see what it’s like to have to explain and defend your beliefs to people who

think you’re basically nuts. You also get to see things like Mormon underwear,

which I’d never really seen…in fact, I didn’t know such a thing even existed. I

just thought, Boy, these guys have some heavy-duty industrial knee-level

chastity underwear that looks like it should also come with a padlock or alarm system

should anyone come close, like Princess Vespa in Spaceballs. Not very erotic,

but the film manages to find plenty of eroticism anyway. It doesn’t hurt that

the two leading men are lookers.

We get a

curveball in the Brian Allard character, a pot-smoking Iraq war vet with PTSD,

who RJ and Chris get to know as part of their outreach. Rodney (Allard) is not

religious at all, and on the surface, looks like a potentially bad influence on

these two young men of God. Indeed, by film’s end, he’s got them smoking pot

and watching R-rated movies. A change starts to take place in these characters’

lives as they reexamine their priorities, which affects their performance as

missionaries and jeopardizes the secret relationship that they share.

Soon comes a

crisis point. I won’t say what it is, but it’s fairly predictable, inevitable

really. Soon we meet the families in the wake of said crisis, as everyone must

decide where to go from here. We meet Harold Phillips, who is Portland’s answer

to Tom Hanks, that affable guy whose face is always welcome in any movie or TV

show. He plays the father of RJ, who is the more fortunate of the two lovers in

that he has a fairly supportive family that is capable of adjusting. Chris does

not. All of a sudden, the romance between the two men is subject to the

dictates of God, the church, family, friends, and probably the dog as well.

Will it survive? Who can know?

And that’s

where they leave it. And to think, writer/director Jon Garcia—who is neither

Mormon, nor gay—wasn’t originally going to follow it up with a sequel. But his

film resonated with people, much more so than he could have imagined.

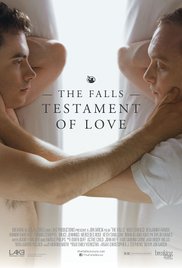

The Falls: Testament of Love (2013)

Part 2 is

the most challenging of the trilogy, both for the characters themselves and for

the audience. It’s an excellent film, but it is not an easy film to watch; it

is actually grueling at times. And it is due to the honesty and the genuine

humanity that is shown in every well drawn-out and nuanced performance.

Five years

after the events of the first film, RJ and Chris have moved on with their

lives. Chris has been pressured into reparative therapy, which paved the way

for a marriage with a beautiful woman (Emily, played with real tenderness by Hannah Barefoot), a

marriage that seems happy, but the audience—who always knows more than the

characters do—understands it’s an ill-advised union based on lies and

self-denial. They even have a kid and a lavish house, which is not quite as

nice as the one the Cullen family owned in Twilight, but almost. (Where are

these beautiful local homes, wonders the Portlander.)

RJ has also

begun a new relationship with personal trainer Paul (played with heartbreaking vulnerability

by Thomas Stroppel), and they reside in Seattle. The relationship isn’t perfect.

You get the sense that Paul wants to change RJ in certain ways, to mold him

into what he thinks he ought to be—eating better, exercising more, etc. It’s

nothing compared to the pressure that Chris is enduring, but there is an

unsettling disparity in terms of what they both want from the other, in spite

of the very real affection that is apparent in their interactions.

What

reunites RJ and Chris is the death of their old pal Rodney of cancer (although

the cancer is only explained in a deleted scene; in the theatrical cut, I don’t

think we even know what he died of). It’s an awkward reunion, and Chris has

repressed his sexuality to the point of hostility towards RJ when it’s brought

up. That hostility is intensified a few weeks later when RJ decides to take a

trip to Salt Lake and drop by Chris’ house uninvited and unannounced in the

middle of family dinner, setting off a series of events that threaten to blow

up Chris’ family to smithereens.

One of the

challenging things about this series—and most particularly, this installment—is

that these people are revealed to be not constantly lovable paragons of virtue,

but really deeply flawed human beings, sometimes incredibly selfish, incredibly

reckless and irresponsible. There are several actions taken by both Chris and

RJ that may seem very wrong to some viewers, including myself. You want to root

for these people, but you sit in front of the screen just a little aghast at the audacity of some of these choices that are made. “Why did he just do that?!”

you yell to yourself. And even I had to remind myself that these people,

through no fault of their own, have been put into an extremely difficult

circumstance, in which their very faith and eternal salvation may be at stake,

not to mention their relationship with their families and communities, and

balancing with that the question of the very legitimacy of true love. In

extreme circumstances, people respond in extreme and desperate ways. You can’t

really judge them too harshly because you can see every fragment of love, fear,

anger, confusion, and despair in the faces of both RJ and Chris (in some of the

most truthful and sensitive performances I’ve ever seen from Ferrucci and

Farmer, who should go on to become enormously successful and famous because

they deserve it). The same goes for the heartbroken Emily and Paul, who had

the misfortune of being forced rebound relationships doomed to destruction by

the on-again, off-again chaos that is this tortured romance.

There isn’t

any hero or villain here. You genuinely come to feel for every character in

this story, much more than in Part 1 because the stakes are so much higher.

There is no way for anyone to come out of this unscathed, no way to avoid pain

and heartache. Whose fault is it? Some of it lies in the church and the belief

systems that oppress its members, but it also lies squarely in the hands of our

protagonists, who don’t know how to find peace and happiness in a way that

avoids running over the people they care about.

Not a

feel-good movie, but a powerful one.

The Falls: Covenant of Grace (2016)

First off,

one of my favorite film titles, ever. And very appropriate because if anyone

needs grace, it is Chris, RJ, and their families.

In between

seeing Part 2 and the filming of Part 3, I reached out to Ben Farmer by email,

telling of how much I admired these movies. I’m one of a great number of people

who have done this, generating the overwhelming response that encouraged the

making of both parts 2 and 3. My friend Michael Stringfield, who produces

sports programming but does occasional commercials on the side, asked if I

would be an extra in a shoot for Eastside Distillings Burnside Bourbon, and

because I have a hard time saying no to anything Michael asks of me, I showed

up at this bar, and was surprised to see Ben Farmer as the main character in

the commercial. It was a weird day because I felt like this closet groupie

wannabe fanboy, wishing I would will myself to go schmoose with this actor that

I was so impressed with, but I was too shy to do so. I resolved that he would

someday act in one of my stage productions, but I would soon find out he was

moving to New York. A few months after that, they started filming Covenant of

Grace, and again part of me wished I could be an extra or something, but stayed

away. I didn’t even attend the premier, which wasn’t a real premier because it

was unfinished, but Farmer and Phillips were there, and it would have been fun.

Personal

story aside, this takes place a year after RJ showed up in Salt Lake and tore

Chris’ family apart, then left him alone to deal with the fallout. They do

reconnect, and again, a death serves as a catalyst to the changes that happen in

their relationship. This time, it is Chris’ beloved mother, who was supportive

of him back when his dad was so harsh and judgmental. We see the life that RJ

has built for himself in the last year, now in Portland. He’s got a pair of

lesbian friends who seem a little out of place in this story. (Garcia has given

them a lot of backstory, not all of which is included in this film to help the

audience understand why they’re even there, and if fact, they should probably

just have their own film.) Another new character is Ryan, a younger man who

looks up to RJ and, in fact, has feelings for him. All these performances are

very strong, especially Curtis Edward Jackson as Ryan, whose story closely

mirrors that of Chris and RJ’s. But excellent performances are no surprise at

this point; they are par for the course in these films. You’ve got to credit

Garcia with having an eye for raw talent and clearly a gift for bringing out

amazing work in his actors.

For the

first time, it seems as though Chris and RJ have a real chance at the

relationship that has eluded them for so long. Their family’s views are

softening (with the exception of Chris’ angry brother, played by Andrew Bray in

a role that may be one of the weakest in terms of the writing…Why didn’t Garcia

give this character more dimension than homophobic anger and hostility?). But

the church’s stance has been the opposite. Now there is a new proclamation from

the church which states that children of gay couples can’t be baptized. This

triggers the central conflict of this third installment, which is RJ and Chris

having to finally answer for themselves that question that has been hanging

over them for 7 years: how do they reconcile their faith and their love for one

another? Can they have both?

If that was

the only issue that this movie takes on, it would be a little redundant and

tedious at this point because, like I said, it’s been right there in front of

them the whole time. But this is a movie about relationships more than anything

else. It’s not about preaching social, religious, or political viewpoints. It’s

about the process of self-discovery, figuring out what you really want, what

you really believe, and how you want to treat the people in your life. In what

is arguably the most powerful scene, which oddly doesn’t even feature Ben

Farmer, RJ and young Ryan are exploring their feelings for each other, and instead

of just following the passion of the moment and the true affection that the two

share, like you would expect from RJ (because, you know, we think we know him

pretty well at this point), RJ puts on the breaks, realizing that taking that

relationship to a physical level would only hurt Ryan because of RJ’s

unresolved feelings for Chris, and because of Ryan’s similar situation with his

own former missionary companion over which he pines day and night. This is a

real evolution for RJ’s character, and it’s incredibly refreshing.

Chris has a

similar moment with his father, from whom he has been seeking approval all his

life. Once he gets it, he realizes that’s awesome, but even if that had not

been given, he had come to the place where he could make his own decisions and

be at peace with them.

Eventually,

RJ and Chris decide what they’re going to do. Will they be together, at last?

Obviously, I’m not going to say. What I will say is that Covenant of Grace is a

satisfying conclusion to this beautiful and emotional story.

So what more

is there to say about these films that I haven’t said yet? For me, it’s all

about honest, totally invested performances, characters that feel so real that

you almost believe you know them personally. It’s also the writing. While this

material could have come across as fairly pedantic, Jon Garcia seemed more interested

in telling a compelling story than in preaching any particular point of view. There

are Issues, but they always take a back seat to the relationships, and that’s

how it should be. That’s why I think a lot of films of this type fail is

because they are throwing a sermon at you instead of engaging you in a very

personal and relatable story. There is so much honesty and truth in these three

films, it would take a hundred mainstream Hollywood movies to match it.

See these

films. See them with friends and family. And then have them encourage others

to. And, you know, I’ll get mine out eventually.

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Denial by Richard Strife

How do you escape an unhappy life? For Rebecca Silas, the young woman at the center of Richard Strife’s debut novel, Denial (Book I of a series called The Drakeon Chronicles), the answer is desperate and extreme. It is not enough to leave the man she’s about to marry at the altar; she’s going to leave this whole world behind. Fortunately for her, she has an annoying little brother named Alex who stops her in the act. But escape still comes in the form of a ghost dragon that appears out of nowhere and whisks Rebecca and her brother into a mythical world called Gaedia.

So begins

one of only a few fantasy novels that I have read. I generally avoid them

because they require more concentration—and perhaps even a little more

imagination—from the reader who must memorize all kinds of foreign-sounding

names, places, and things, in addition to filling in a lot of the mental details

about descriptions of creatures and landscapes because if the author were to

take the time to create a truly vivid picture for the reader, the novel would

be 1,000 pages long. (And yes, I realize some are, and many fans have no

problem with it!) One of the greatest

strengths of Denial is that it is

accessible to folks like me, who usually prefer reading about the familiar to

the otherworldly.

The idea

that you can accidentally step through an unknown portal and end up in another

world (or, in some cases, a parallel universe) is not a new one; it’s a

tried-and-true convention of the fantasy and sci-fi genres, from Star Trek to The Dark Tower. It works best when the starting point is that place

that you’re familiar with already. It grounds you in the story and characters

so that when it’s time to take the journey to the unknown, you’ve got something

that feels concrete to hold onto.

When Rebecca

and Alex arrive in Gaedia, they find a world in extreme conflict, where dragons

are massacring the townspeople left and right, in violation of an old treaty.

We meet the handsome, charismatic prince Sebastian, who chases one such dragon

away with his mind control abilities. Sebastian is on a mission to find his

missing father, the future Emperor, but he also needs to get to the bottom of

what’s going on with these attacks. Meanwhile, Rebecca meets a wounded female

werewolf—or Lykos—called Kaece, who she helps flee from town undetected. Sebastian’s

people, the Maedians, and the Lykos share a mutual hatred for one another. This

is a central conflict in the story, as Rebecca and Alex need Sebastian’s

protection in the wild continent of Xiratera, but Rebecca has formed an

immediate and obsessive affinity with Kaece, which could prove deadly.

As Rebecca,

Alex, and Sebastian travel the continent in something called a Hadros (a

vehicle that will likely remind the reader of the All-Terrain Armored

Transports used by the Empire in the Star

Wars films), with a dangerous and seductive Lykos on their tail, they will

get to the bottom of what’s happening to this now-threatened world, and in the

process, fight dragons, fly through the air on mythical creatures, witness the

unimaginable destruction and carnage of war, and discover a great deal about

themselves.

Denial is a coming-of-age story, although I

hesitate to call it a YA book because of the amount of graphic violence and

sexual content. This is not Tolkien or C.S. Lewis; it’s more like Stephen King,

and it might be disturbing to sensitive readers.

The story is

told through four points of view, and the author is rather clever in the way he

subtlety switches some stylistic elements chapter by chapter, depending on what

character we’re following. He could have distinguished the characters even more

if he had written one of them in first person perspective. But that’s a small

matter. The one distinction that isn’t remotely subtle is that Alex’s chapters

are in comics form, which is appropriate considering the character’s age of 13.

Comics are

another thing I avoid, for a similar reason that I avoid fantasy. They take

effort to get through and interpret correctly, to figure out what’s going on in

the scene. The artist has to tell the story clearly with a limited number of

frames, and I would be lying if I said that I could always tell in this book exactly

what I was looking at. But I usually could, and that is a credit both to Strife’s

drawing talent and his ability to tell a story visually.

The

characters are all unique and yet relatable in their own way. As a reader, I

changed my opinion about various characters several times. For instance, I

found Sebastian to be initially self-righteous and arrogant, but he grew on me.

Kaece was not immediately likable, and the author’s decision to always have her

say “ya” instead of “you” is something I found rather distracting, but by the

time I was halfway in, I felt more for her, on an emotional level, than anyone

else in the story. It was the contrast of the tough exterior but vulnerable interior

that make her the most intriguing.

Strangely,

Rebecca and Alex seem under-developed and ordinary by comparison, and not simply

because they are human. Rebecca has all the teenage angst and drama you would

expect, all the emotions running wild in a thousand different directions,

struggling with self-esteem, confusion over sexual identity, and rebellion

against other people’s expectations of her. And her brother, well…He’s simply a

precocious 13-year-old wanting to prove his worth and bravery, but in spite of

his chapters being illustrated, his story is somewhat one-dimensional. Why don’t

these two ever think about their parents, or their home lives? Aren’t they

worried about their families or friends? Aren’t they grieved at the notion of

never being able to return home? Rebecca engages in self-pity over failed past

relationships, but we get no sense of what life had been like for the siblings,

beyond that.

Overall, the

novel is fast-paced, engaging, and unpredictable. As the story unfolded, I

could never tell where it was going, nor what would happen next. There are many

unexpected twists and turns. And it’s a bit of an emotional roller coaster as

well because the stakes are very high for some of these characters, not only in

terms of what may happen to them, but in terms of the revelation of who they

really are, and what that means. Some big questions are asked: Does love

override duty and loyalty? Do ethics matter in wartime? Are there some things that you can’t forgive?

As a gay

guy, I didn’t love the lesbian romance aspect of the story (I’ll always prefer

stories about dudes), but it was very intense and relatable. Rebecca has some

self-loathing that she has to get over, and that’s pretty universal, I think.

Creationists

may take issue with an explanation for Earth’s origin other than the one found

in the Book of Genesis. I know I did, even though you can easily answer by

saying “it’s a fantasy novel, not a theology text”. I don’t know, for some reason

it just nagged at me, probably more than it should, like an itch that you can’t

reach to scratch.

But by and

large, this is a thoughtful work of fantasy fiction, and full of heart, a labor

of love for an author who loves a good story, and who loves the people he’s

telling it to.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)